Part I, Book 1, Chapter 4

Deeds to Match Words

What a journey this chapter takes us on. It begins with an accounting of the bishop’s sassy moments, and ends with some pretty profound reflection on the damage the work enacts on his soul.

Like the previous chapter, this is more character study than story. Hugo relates several anecdotes featuring the bishop’s “gentle mockery,” and it’s clear this is a man who delivers iconic one-line zingers like Dorothy Parker or Winston Churchill. I’m convinced Monsieur Bienvenu would have made an iconic shitposter.

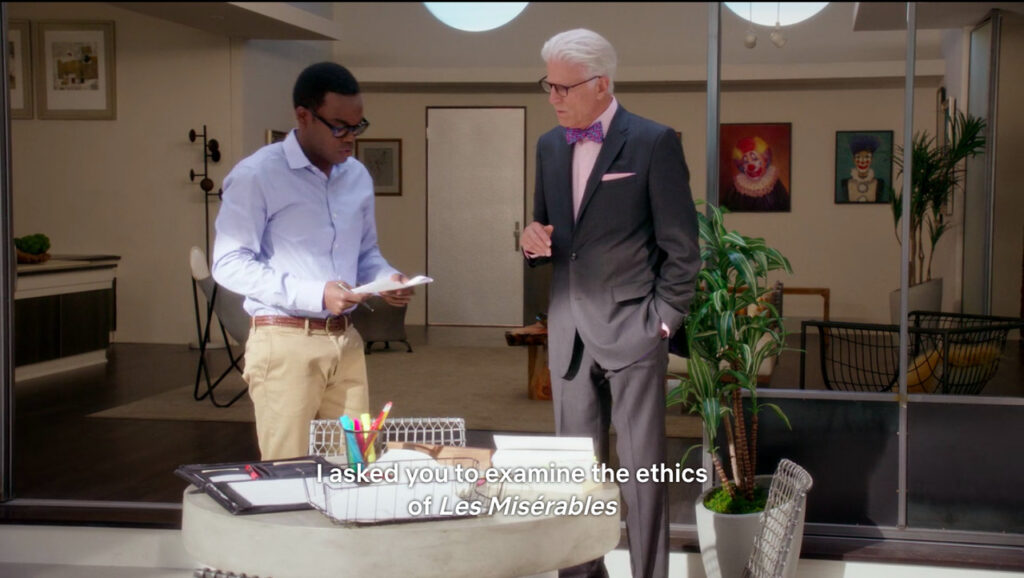

As the best shitposters do, our bishop punches up, not down. He doesn’t dunk for the sake of dunking, or to prove his own superiority; his spiciness is rooted in a desire to make people aware of their own hypocrisy and selfishness. He doesn’t expect people to be perfect saints, but he wants them to aspire to goodness, and I now understand why Chidi assigned this book to his ethics students on The Good Place.

He also identifies society and its systemic ills, not people’s personal failings, as the root cause of so many problems, and points out that people trapped in ignorance by larger forces cannot be expected to bootstrap themselves out of wretchedness.

In other words,

For if you suffer your people to be ill-educated, and their manners to be corrupted from their infancy, and then punish them for those crimes to which their first education disposed them, what else is to be concluded from this, but that you first make thieves and then punish them.

That’s a quote from Thomas More. I wish I could tell you that I know that quote from having read Utopia, but I learned it from Drew Barrymore’s character in the movie Ever After.

Then we move onto some of the heavier aspects of the bishop’s job. There’s a man sentenced to death, and the local parish priest refuses to attend the man in his last moments because he’s just not feeling it. So obviously our sweet Myriel goes instead, and finds the man—as anyone would be—facing death in agony and despair. The bishop spends all day and night, forgoing food and sleep, with a man that other jagoff priest wrote off as not being worth his time, and guides him out of despair and into a dignified place of peace.

The next day both walk calmly onto the scaffold together, and the bishop stays by the man’s side even as the blade drops on the guillotine. The serene radiance of the bishop makes a huge impression on everyone who witnesses the execution.

“As for the bishop,” Hugo writes, “it was a shock for him to have seen the guillotine, and it took him a long time to get over it.”

What follows is a passage about the sheer monstrosity of the guillotine that you cannot know until you have seen it meting out its brutal judgment yourself, and the feeling of lived experience is so strong in these sentences that it’s like the story has melted away for a moment and you’re getting Hugo himself, direct and urgent, begging you to understand how horrible the guillotine is, in what it does and what it represents.

The bishop, Hugo wants us to understand, is deeply traumatized by the work he appeared to have done so calmly. “[F]or many days afterward the bishop seemed devastated. […] The phantom of social justice haunted him.”

Up until this point the bishop’s goodness has seemed almost superhuman; this chapter is where we understand the toll of giving so much of himself to others. It’s a strangely beautiful reminder that sensitivity is not weakness, and that even the best among us struggle with the weight of our burdens.

Leave a Reply