Part I, Book 2, Chapter 3

The Heroism of Passive Obedience

Valjean opens the door to the bishop’s house and appears on the threshold, looking absolutely terrifying. I cannot help but picture Darla’s entrance in Finding Nemo.

When I say he looks “absolutely terrifying,” I mean that Mademoiselle Baptistine and Madame Magloire are terrified. The bishop is totally chill.

Valjean launches straight into an explanation of who he is. This is both understandable in the story—each time he’d nicely asked for food and a place to sleep, expecting to be treated like a normal human being, he ended up humiliated and thrown out, so he might as well just get it over with—and works to great dramatic effect.

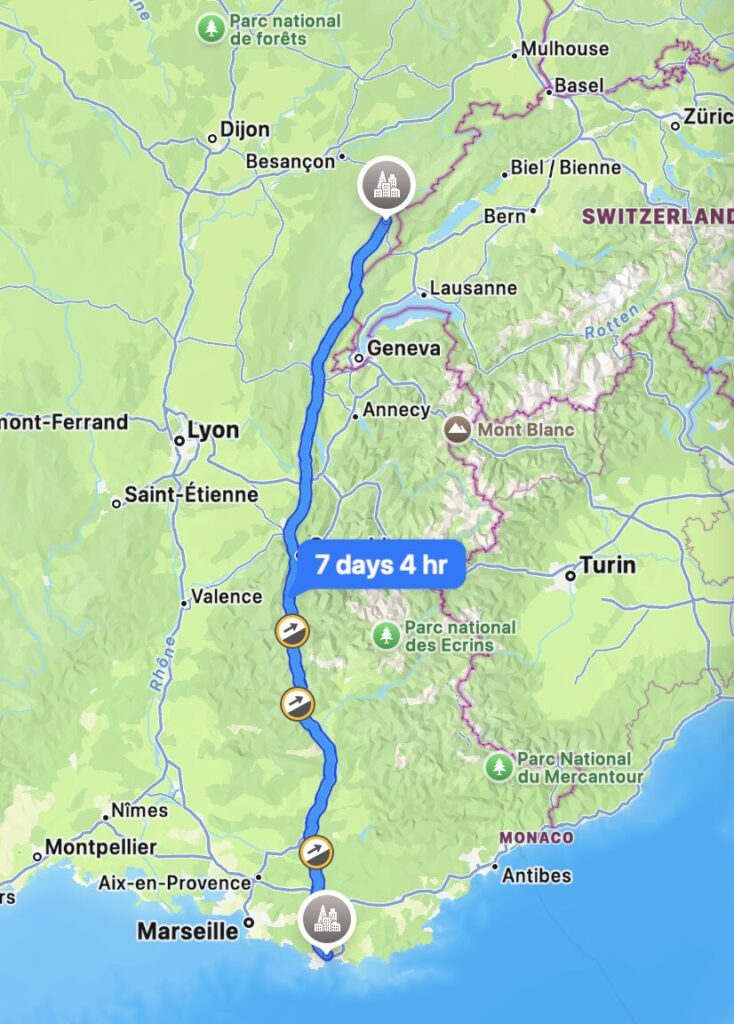

Very little of the information he immediately offers about himself is new to anyone who is a fan of the musical or who read the first chapter of Book 2. He is an ex-con who spent 19 years in chains, was freed 4 days ago in Toulon, is headed to Pontarlier (at this point I am seriously thinking about keeping a Les Mis map so I can track this stuff), and has been walking for all 4 days of freedom. Today he’s walked 36 miles alone. I am exhausted just thinking about it but also wondering how, in a time before smartwatches and pedometers, how he knows he’s walked exactly 36 miles.

Also, out of curiosity, I looked up the distance from Toulon (where Valjean started) to Pontarlier (where he’s headed) and Apple Maps says it’s over 7 days of nonstop walking on modern roads. Holy hell.

He also explains how everyone knew to throw him out; when he arrived in town, he went to town hall and showed the yellow passport identifying him as a convict, which he is legally required to do, and because everyone in town got wind of it, he was turned away everywhere he went. He proceeds to summarize Chapter 1, which we don’t have to rehash here.

Valjean, offering to pay (“What is this place? Is it an inn? […] I have money. I’m very tired, thirty-six miles on foot, and I’m hungry. Will you let me stay?”) explains that he has money: his entire savings, 109 francs and 15 sous, which he earned over his 19 years of work on the chain gang.

I am not entirely sure how much a franc is worth out of context, but based on the fact that the bishop gets a 15,000 franc salary plus a 3,000 franc transportation stipend for a grand total of 18,000 francs per year, the fact that Valjean got just over 100 francs for 19 years of hard labor is galling. (I just did the math, and Valjean’s 19 years of pay amounts to 0.6% of what the bishop gets in a single year. Christ.)

The bishop responds by calmly asking Madame Magloire to set another place at the table. I love Myriel’s zen energy here and also this cannot be the first time he’s done this.

Valjean is half-convinced the bishop didn’t hear the “hi I’m a criminal” part of his monologue, so he asks, point blank, if the bishop didn’t hear what he said, and repeats the fact that he’s an ex-convict from the chain gang and shows his yellow passport. He mentions, somewhat heartbreakingly, that he can read what the passport says because he learned to read in prison school, and proceeds to read off the words on the passport identifying him as a “very dangerous” man. “Have you a stable?” he finishes.

Oh Valjean! It kills me that you’re reduced to asking for room in a stable. The thing about stables is 1) they’re not insulated, and 2) even horses get blanketed in stables, because see point 1. I literally just tied two layers of blankets on a horse yesterday so she would make it through a night of Southern California winter, and Valjean is in a town in the French Alps that Hugo keeps telling us is very cold.

It is also horribly dehumanizing when stables are used for human habitation; I thought about the fact that stables were repurposed as family dormitories in the Japanese internment camps, which is just one terrible detail in a sea of violations that was one of the most fucked-up things the US has done to its own people in living memory.

The bishop responds to Valjean’s question about the stable by asking Madame Magloire to make up the spare bed with clean sheets. He then tells Valjean to sit down and get warm by the fire, and that he’ll have supper and a bed to sleep in. Absolutely stellar example of a man, that bishop.

Valjean is completely stunned. “I’m going to eat tonight! A bed! […] It’s been nineteen years since I slept in a bed!”

I was reminded, with Valjean’s exclamations of shocked joy, of the scene from Frances Hodgson Burnett’s A Little Princess, when Sara Crewe gives a bag of hot buns to the starving beggar girl on the baker’s doorstep. It’s even more poignant of a scene because Sara herself is impoverished and starving, which parallels the bishop’s voluntary poverty.

The entire time, Bishop Myriel addresses Valjean as “Monsieur,” which is really touching: “‘Monsieur’ to a convict is like a glass of water to one of the shipwrecked survivors […] Ignominy thirsts for respect.”

Valjean expresses astonishment that the bishop is being so good to him even after Valjean explained his backstory, and the bishop says, “You didn’t have to tell me who you were. This isn’t my house,” (shadows of “You’re in my house and I’m in yours“), “it’s the house of Jesus Christ. […] Everything here is yours.”

Move over, Gimli, the famed hospitality of the dwarves is nothing compared to the bishop’s game!

Quick aside that the bishop goes on to say “before you told me, I already knew your name,” and Valjean goes omg really?!?! and the bishop says, “Yes, by the name of ‘Brother.’” First of all, big youth pastor move. Second of all, this must be the source of the line in the musical: “He gave me his trust, he called me ‘Brother.’”

All of this goodness and generosity is overwhelming to Valjean. And me—I’m getting whiplash going from the unnecessary cruelty of Chapter 1 to this. And so Valjean says, in an outburst of effusiveness, that all the bishop’s goodness has erased his hunger.

At this point, I was a little unsure of Valjean’s sincerity—he’s so full of grateful exclamations in this chapter, and the sentiment is surely real, but the line from the musical, “I played the grateful servant / Thanked him like I should,” has planted the tiniest seed of skepticism in my head. Is all of this an act? Guess we’ll have to see.

The title of this chapter, “The Heroism of Passive Obedience,” is surely in reference to MVP Madame Magloire, who despite her personal fears takes all of the actions to follow through on the bishop’s hospitality; she brings out a whole spread of modest food and adds, on her own initiative, some wine the bishop doesn’t even drink himself (it’s too fancy for him). She also, on the bishop’s cue, brings out the silver candlesticks and all six sets of silverware for the sake of making the table look really nice.

Oh yeah, now we’re cooking.

Leave a Reply