Part I, Book 2, Chapter 13

Petit-Gervais

It’s a good thing we’ve banked a lot of sympathy for Jean Valjean in previous chapters, because this chapter was not him at his best. Chapter 13 is where Valjean ROBS A CHILD.

A LITERAL CHILD.

Let’s back up a bit. Valjean has just fled town after experiencing the Most Bishop anyone can ever get, and he is overwhelmed with emotion. “Overwhelmed” might be an understatement; he’s gone from being emotionally numb for 19 years to getting whacked with more feelings than most people normally feel in a year, all at once.

You know how in Inside Out, all the different emotions take turns rewatching memories and punching buttons on the control panel?

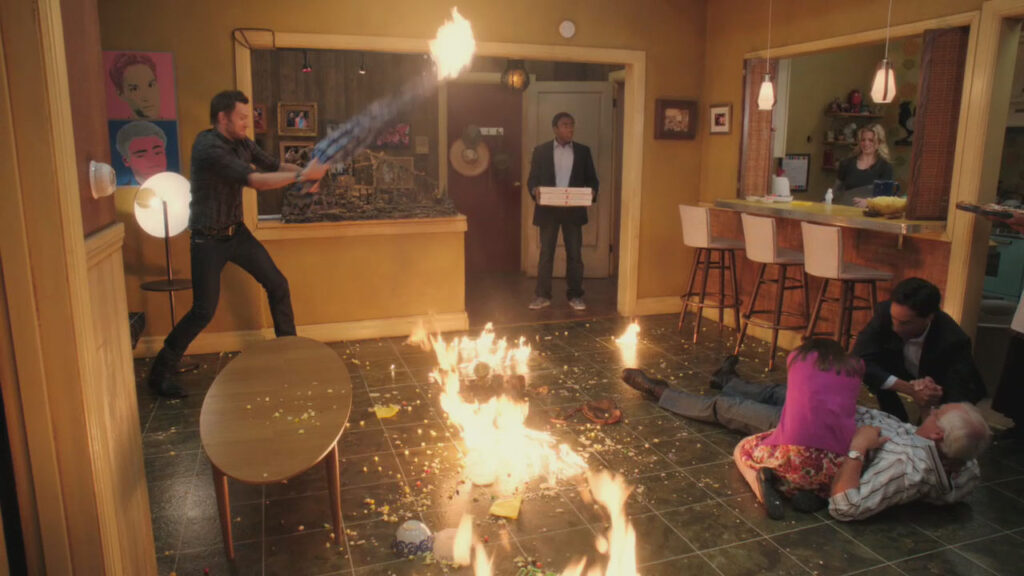

I can’t imagine what HQ looks like in Valjean’s head at this point. It’s utter chaos. All the alarms are going off. Stuff is probably on fire. It probably looks more like this:

“At times he truly would have preferred to be in prison with the gendarmes, and for things not to have turned out like this. It would have been less disturbing.”

Valjean has been all alone with his big feelings trekking through a middle-of-nowhere plain in the Alps all day, when around sunset he hears “a joyful sound.”

Said joyful sound is a 10-year-old boy, with a marmot and a hurdy-gurdy, “[o]ne of those sweet, blithe little lads who go from place to place,” which I have to say sounds extremely adorable even as it is incredibly worrying. 10-year-olds shouldn’t roam around the countryside busking for a living, but this is the world we’re in.

The little boy is singing and playing with a handful of coins which is “probably his entire fortune.” I thought this was very dumb—maybe don’t treat the only money you have as a toy—and then I remembered that in high school I would make a game of tossing my Nokia cell phone high up in the air to see if I could catch it, which I didn’t always. So really, who am I to judge?

Of course, one coin—a 40 sou piece—rolls away, towards Valjean, who automatically puts his foot right over it. Right in front of the little boy.

Not a great move, but we all do inexplicably dumb things in front of strangers! The child, whose name is Petit-Gervais (great cat name!!!), asks, “with that childish trustfulness,” for Valjean to return his coin.

Valjean just keeps his foot on the coin and tells Petit-Gervais to go away. Little G keeps asking for it back, Valjean keeps not giving it back, Little G starts crying. Come on, Valjean!

Finally, when Petit-Gervais gets so worked up he starts shaking Valjean in desperation, Valjean stands up and yells at him to get lost. No, really, in my translation he yells, “Get lost, will you?”

Poor Petit-Gervais, who is now terrified of this guy who ROBS CHILDREN, runs off sobbing.

This is a real tough look for our guy Jean Valjean! I completely understand the emotional turmoil he’s facing and how it makes sense for him to behave this way given everything that’s happened in this life before and yet…HE HAS JUST ROBBED A LITERAL CHILD. It was at this point that I texted multiple friends who have read Les Misérables and typed “VALJEAN JUST ROBBED A CHILD WTF” in all caps just to get it out of my system.

Valjean just stands motionless for a while with his foot on the coin as the sun sets, Little G disappears, and darkness falls around him. Then Valjean moves his foot, sees the coin, and finally what he’s just done hits him with full force.

Now Valjean is running wildly through the countryside, shouting Petit-Gervais’ name, trying in vain to find him to return his coin. Buddy, have you seen how fast children can run? That poor kid is probably halfway to Italy already.

Valjean ends up running into a priest on horseback, and asks the priest if he’s seen Petit-Gervais—the priest has no freaking clue who he’s talking about, and Valjean, in emotional turmoil, throws 10 francs of his own money at the priest and tells him to give it to the poor. He keeps describing Petit-Gervais—my guy, a little boy with a marmot and a hurdy-gurdy is pretty memorable, if this priest hasn’t seen him, he hasn’t seen him—and throws another 10 francs at the priest for the poor. I did the math, and that right there is 18% of what he made in 19 years’ worth of hard labor.

Finally Valjean says, wildly, “Monsieur l’abbé, have me arrested. I’m a thief.”

I do feel so bad for Valjean at this point. His shame and guilt have gotten so intense here that it’s broken his brain–at this point he’s just reflexively trying to undo the bad thing(s) he’s done by whatever random act he’s capable of in the moment.

The priest, understandably (because he’s not the bishop and we all know the bishop is not normal), freaks out and rides away. Valjean keeps running and calling Little G’s name, before he finally collapses and weeps for the first time in 19 years.

I actually feel bad now. Valjean, I’m sorry for calling you a child-robber.

As Valjean weeps in the desolate darkness (what’s that literary term for when a physical environment reflects a character’s inner feeling, because this is definitely that), the bishop’s words about buying his soul for God keep coming back to him.

He becomes vaguely aware that he is, at this point, at a crossroads, faced with an active choice about who he is to become. “That this time he had to vanquish or be vanquished, and that the battle had been joined […] between his own wickedness and that man’s goodness. […] For him there was no middle ground any more: after this, if he were not to be the best of men, he would be the worst.”

(Some therapists might identify this as black-and-white thinking, but you can’t deny it makes for great literature.)

It’s really interesting to me how Hugo frames the impact of the bishop’s act of extreme kindness on Valjean—he uses words that connote a level of violence. “[T]his priest’s forgiveness was the greatest assault and most tremendous attack he had ever experienced” is one way he describes it, and then a little while later he writes, “[T]he bishop hurt his soul when he came out of that perverse place of darkness.” Hugo seems to be pointing out that the sheer extremity of the bishop’s act is essentially a shock that Valjean is almost completely unequipped to handle.

Hugo also explains, for the readers in the back who maybe have more trouble grasping the paradox of human feeling, why Valjean acted the way he did, and why he ended up in such agony. “[I]t was not he who stole […] it was the beast that out of habit and instinct had stupidly put his foot on that money while the thinking mind was grappling.”

And the reason this last theft breaks him so, Hugo goes on to explain, is because “by stealing money from that child he had done something of which he was no longer capable.” Even deep in the confusion of his emotional turmoil, Valjean had already been changed.

Because therapy isn’t an option for Valjean (and oh, how badly I want this poor man to get therapy), he needed—perverse as it seems–to commit one “last bad deed” to gain awareness and clarity of who he is and what choices he has before him. You could argue—and I think Hugo has been doing so all along—that Valjean’s first crime was not one of active choice. Battered first by poverty and then by harsh punishment, he would have continued his whole life to act without self-awareness out of fear, anger, and need, if the bishop hadn’t careened into him the way he did.

In Valjean’s mind’s eye, as these things start to clarify for him, he sees the bishop filling “this wretched man’s soul with a magnificent radiance.” Valjean weeps even more. Between the full day of walking and all the crying, I am worried that he is severely dehydrated and I want to run to him with a chilled bottle of electrolyte water.

In this last bout of weeping, Valjean sees his life clearly. “He beheld his life and it looked horrible, he beheld his soul and it looked dreadful.”

The chapter, and Book 2, ends with Valjean kneeling as if in prayer in the darkness at the bishop’s front door.

WOOF. Despite my initial “WHAT THE F, VALJEAN WHAT ARE YOU DOING” reaction to this chapter, I actually really loved it—it has way more impact than Valjean’s turn towards goodness in the musical, because it feels so much more human and realistic. It makes less sense for Valjean to have changed just from being given the silver—of course he would have to pass through this crucible if he is to entirely change direction from the path that 19 years’ imprisonment had forged for him. He had to be shown who he has become, and unfortunately for Little G, stealing an innocent child’s money is how it had to happen.

It is also really interesting to consider that, ultimately, it isn’t punishment that catalyzes this shame and awareness for Valjean, but a radical act of kindness. Seems like Hugo is trying to tell society something!

Leave a Reply