Part I, Book 4, Chapter 3

The Lark

It will not surprise you that the Thénardiers, scammers of the bastard class that they are, immediately burned through everything Fantine gave them upfront. I know Fantine had no way of knowing and was just doing her best, but GIRL, this is why you don’t entrust your child to randos based on 10 seconds of vibes!!!

Having used Fantine’s deposit to pay off a debt, the Thénardiers immediately take the beautiful baby clothes that Fantine sewed from her old finery and pawn them for 60 francs. They then dress Cosette in Éponine and Azelma’s discarded old undergarments. Afterwards, they begrudge any expense that Cosette incurs and consider her a charity case, feeding her scraps (!) that she has to eat under the table (!!) with the dog and the cat (!!!…well, that sounds kind of cute, ngl).

(Hugo’s exact words for what Cosette is fed are “a little better than the dog, a little worse than the cat,” and I find it very funny and very on brand for cats that the cat eats the best of them. Hugo is not beating my cat guy allegations.)

Fantine (who is illiterate, remember) hires someone to write a letter every month asking how Cosette is doing. The Thénardiers write every time, “Cosette is thriving.” And Fantine just takes them at their word!

After the first year, Thénardier decides Cosette isn’t bringing in enough money (because they promptly use up all of Fantine’s payments, obvs) and demands 12 francs per month, up from 7. Fantine pays that without complaint, of course. Then when they sniff out the fact that Cosette might be an illegitimate child, they jack up the fee to 15 francs a month. For anyone doing the math, that means Fantine is paying more in a year for Cosette to be mistreated than Valjean earned in 19 years doing prison labor.

I was curious about how much 15 francs was, in context, so I looked it up, and if we go by the fact that an unskilled laborer could expect to earn 1.1 francs a day, 15 francs is possibly half a month’s worth of pay.

This kind of reminded me, by the way, of how city slumlords actually make more money renting hovels to poor tenants than they do maintaining decent apartments and renting to middle-class professionals. One can make a lot of money exploiting poor and desperate people, and this has apparently always been that way!

If you couldn’t tell from the way Cosette is treated (rags! scraps under the table!), Madame Thénardier hates the little ward she is getting paid to care for; she treats the little girl as a scapegoat, an emotional (and physical, sounds like) whipping boy, while doting on Éponine and Azelma. This is great for all three girls’ psychological development.

When Fantine starts falling behind on payments—which of course she does, because she is a beaten-down single mom paying 15 francs a month on top of her own expenses—the Thénardiers put Cosette to work, because child labor laws are not a thing yet. As a five-year-old she becomes a servant. FIVE YEARS OLD.

Three years after being dropped off with the scammy innkeepers (Fantine!!! Check on your child!!!), Cosette is unrecognizable. No longer a lovingly pampered little angel dressed like a little lady, “misery had made her ugly.” She is thin, pale, and her huge baby eyes are full of sadness. Ugh.

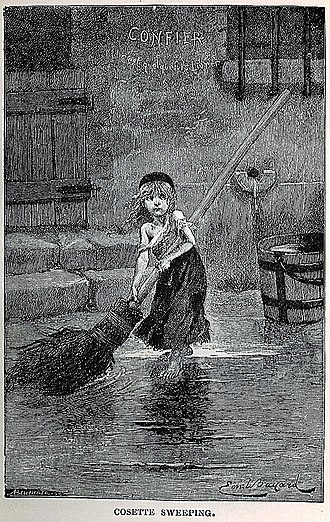

Hugo then presents us with the now-iconic image by Émile Bayard that culturally represents all the wretchedness in Les Misérables:

It was a heart-breaking thing to see in winter, this poor child […] shivering in her tattered old rags of coarse cloth, sweeping the street before daylight with an enormous broom in her tiny red hands and a teardrop in those big eyes.

The locals call her “Alouette,” or “lark,” because she’s a tiny shivering creature first to wake in the morning. Again, FIVE YEARS OLD. I first thought, if everyone can see Cosette’s misery on plain display, why didn’t they do anything about it?!?

Then I remembered Sara Crewe’s fall from grace in A Little Princess, where Frances Hodgson Burnett writes:

A happy, beautifully cared for little girl naturally attracts attention. Shabby, poorly dressed children are not rare enough and pretty enough to make people turn around to look at them and smile.

In the way that Hugo asks us to think of all the Jean Valjeans out there, we can’t help but think, how many little Cosettes have there been, throughout history and today? Our hearts bleed for this one girl, but she is meant to represent all the children who can’t speak up for themselves, who no one intervenes to save because people naturally don’t care as much for “shabby, poorly dressed children.”

Thus ends Book 4. It’s already so sad and I know it only gets sadder from here.

Leave a Reply